In 1941, the Disney animators’ strike emerged as a game-changing event in the world of animation, leaving an indelible mark on the industry. This historic strike not only altered the landscape of American animation but also laid the groundwork for future labor movements, including the recent Writers Guild of America (WGA) strike.

The ongoing WGA strike, which has surpassed the one-month mark, highlights the breakdown in negotiations between the WGA and Hollywood studios. The key points of contention revolve around pension plans, residual compensation for streaming productions, healthcare benefits, and protections for writers in the era of artificial intelligence. Writer-comedian Adam Conover aptly characterizes this strike as a battle for the survival of television and film writing as a sustainable career.

As we witness this current drama unfold, it’s crucial to recognize the significance of past conflicts between collective labor and monopolistic power structures. These conflicts have played a pivotal role in shaping the present state of the entertainment industry. This week, we commemorate the 82nd anniversary of the Walt Disney Animation Studios strike, an event that reverberated throughout Hollywood, triggering a seismic shift in the American animation landscape.

While the Disney animators’ strike was not the first of its kind, as the Fleischer Studios strike of 1937 had already established the industry’s first union contracts, it nevertheless marked a crucial moment for the American labor movement. By 1941, every major animation studio, including Warner Bros. and MGM, had effectively unionized, leaving Walt Disney Animation Studios as an outlier in Hollywood’s labor landscape.

The genesis of dissent within Disney can be traced back to the 1930s and a significant event that propelled the company from a popular animated-shorts producer to a cultural powerhouse: the production and release of “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” in 1937.

The ambitious three-year production of “Snow White” demanded an army of animators, assistants, inbetweeners, layout artists, background artists, special effects animators, inkers, painters, and numerous other uncredited individuals, totaling over a thousand people involved in the creation of this groundbreaking feature film. Delays plagued the production, with the first completed animation submitted less than a year before the scheduled premiere.

To meet the rigorous demands, animators were expected to work long hours with minimal compensation. Overtime work went unpaid until the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 mandated overtime pay for employees exceeding 40 hours per week. In the final push to complete “Snow White” on time, the production staff was informed that their work schedules would be extended, intensifying their frustrations.

The financial stakes were high, with the budget for “Snow White” ballooning from $250,000 to $1.5 million, forcing Walt Disney to mortgage his home to finance the film. Amidst concerns that the film would be a costly failure, Disney verbally promised the production staff a share of the film’s profits—20% to be distributed proportionally based on their contributions and unpaid overtime. However, when the time came, the bonuses received by the artists fell short of expectations, and some, like Art Babbitt, received none at all.

Art Babbitt, a highly regarded animator responsible for iconic characters like Goofy, found himself at the forefront of the strike. The unfulfilled promises and unjust treatment of the animators following the success of “Snow White” fueled his resolve. However, Walt Disney refused to address the pay disparities and other concerns raised by his employees.

Tensions continued to mount within the studio, exacerbated by the commercial failures of Disney’s subsequent features, “Pinocchio” and “Fantasia” in 1940. Financial strain, compounded by the uncertainties of World War II, further heightened the animators’ anxieties.

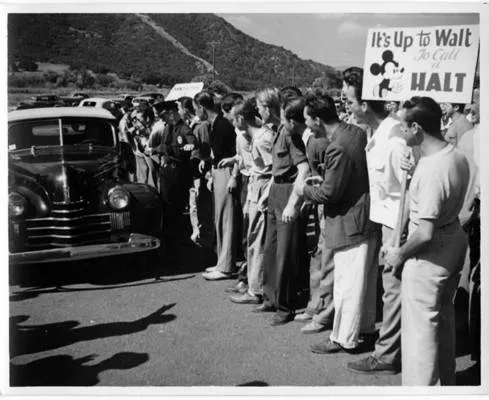

On May 29, 1941, the strike began with a picket line forming outside the Disney studio gates. The artists, led by Babbitt and other key figures, demanded union recognition, a grievance procedure, and a collective bargaining agreement. Walt Disney initially dismissed the strike, referring to the animators as “communists” and “betrayers.”

However, the strike proved to be a turning point. As the picketing continued, Disney realized the detrimental effects the strike was having on his studio’s operations and reputation. On September 21, 1941, after nearly four months, Disney Animation Studios capitulated to the demands of the striking animators. The company recognized the newly formed Screen Cartoonists Guild as the representative of the animators, granting them collective bargaining rights.

While work resumed at Disney Animation Studios, the strike left a lasting impact on the studio’s atmosphere and culture. Friendships were shattered, and many talented animators, including Babbitt, left the company to join rival studios, forever altering the talent pool and creative dynamics in the animation industry.

The Disney animators’ strike of 1941 marked a significant milestone in American animation history. It helped pave the way for future unionization efforts in the industry, ensuring better working conditions, fair compensation, and improved rights for creative professionals. The strike serves as a reminder of the power of collective action and the risks studios face when undervaluing and mistreating their employees.

As the WGA strike unfolds today, its resonance with the events of the past should not be overlooked. The struggles of writers, both in animation and live-action, mirror the challenges faced by the animators of the Disney strike. The demands for fair compensation, healthcare benefits, and protection in the evolving landscape of entertainment resonate with the longstanding battles of creative professionals throughout history.

The current Writers Guild of America strike is a testament to the enduring legacy of the Disney animators’ strike and the ongoing struggle for workers’ rights in the entertainment industry. Whether it is 1941 or 2023, the fight for fair treatment, equitable compensation, and creative autonomy remains a central concern for those who shape the stories we love.

We bring out some of the most well-known Disney collection, all of which are available at reasonable costs. Visit our link now if you are interested in the Disney collection

Mickey Mouse, Minnie Mouse, Donald Duck, Goofy, Pluto