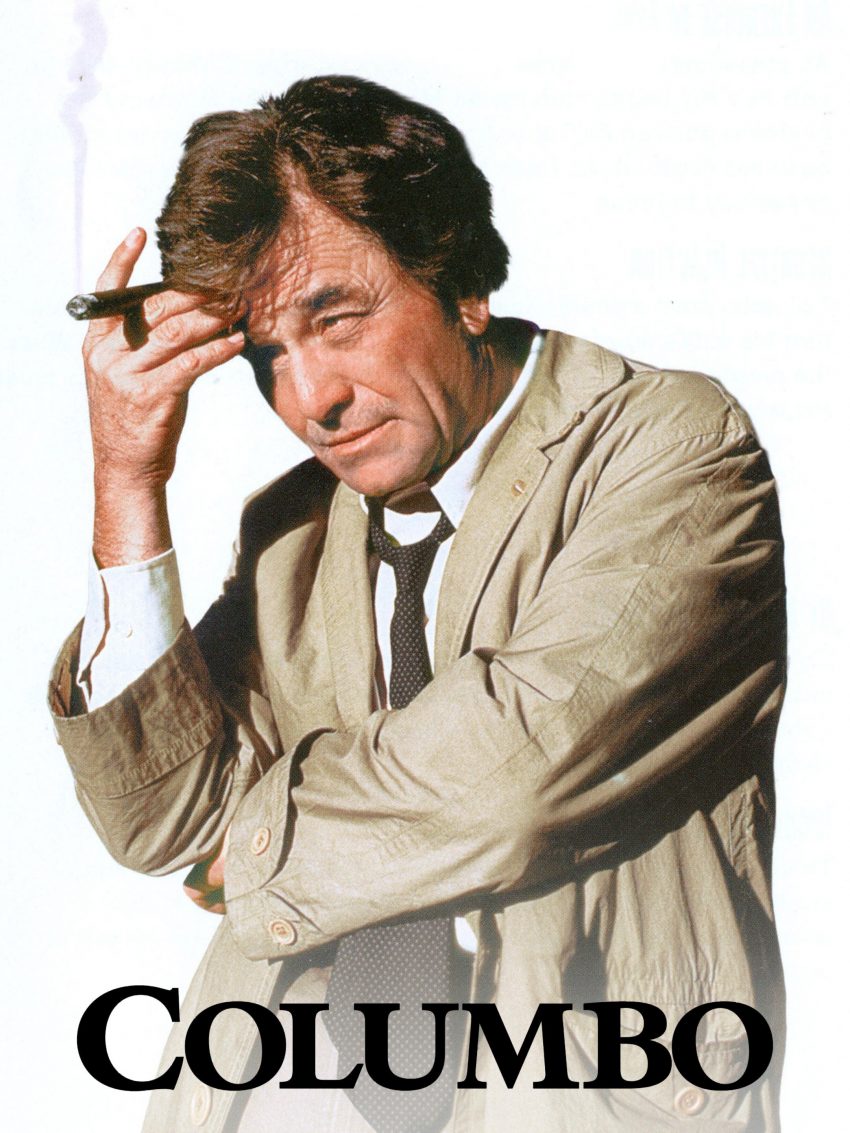

The narrative of Columbo is the tale of Peter Falk. Not Richard Levinson and William Link, who made the show. Not Sid Sheinberg, the Universal chief who greenlit it. Not Patrick McGoohan, who coordinated five episodes, featured in four, and turned into a nearby comrade to Falk. Not NBC leader Dick Irving, nor makers Dean Hargrove and Everett Chambers, nor essayist Jackson Gillis. No; the show’s standing was framed, and later got away, on the rear of its star, a Jew from the Bronx who lost his right eye at three years old and didn’t start to act expertly until the age of 30.

However the job would validate his case for acceptance into the pantheon of incredible TV characters, Falk was at first reluctant to take it on. Cautioned against TV’s one-dimensionality by criminal independent inhabitants John Cassavetes and Elaine May, Falk rather needed to work in films, in workmanship, in The Cinema with all its haughty glory. A model: In 1970 he showed up in one of faction film’s most loved works, Husbands, coordinated by his companion Cassavetes. However he was touched with uneasiness given his freshness with Cassavetes’ improvisational style, the experience was so overpowering, so unadulterated, that it had Falk hurting for additional.

Then, at that point, in late 1970, Falk’s business chief hastened off with $100,000 of his client’s cash. Thus, following a time of supported hassling, NBC, at last, had their Columbo. We like to consider workmanship a heartfelt adjusting of the stars, the result of an unspeakable proclivity between an essayist and their subject, an entertainer and their content, an artist and their thump. Yet, here and there it’s basically as basic as a person requiring a buck.

In spite of his underlying hesitance, Falk before long became associated with the show with a profundity he hadn’t predicted. He would add to the early scripts, lead the cast on set, visit the altering room asking to see dailies. He was fixated. Obviously, fixation is thoughtfully uncertain, and it regularly brings about unpredicted difficulty, shadow-managing, Faustian deals. From the get-go, Falk’s commitment to the show birthed just a final result with convincing solidarity, for the most part, because of his presentation. The aftereffect of this solidarity was an appraisals achievement; the consequence of progress was NBC and Universal becoming subject to Falk to make the show gel; the aftereffect of reliance on Falk was Falk holding the show recover; the consequence of the ventures emancipating was that, via season 7, Falk was making $500,000 an episode – despite the fact that everyone would net NBC just about $400,000 on debuting. At the end of the day, the Faustian deal had been gotten, the handshake irreversible. The possible question left was the point at which Satan would come to gather his levy.

What it forever is, in any case, is top-notch, and generally a fun time. Its recipe, truth be told, has something to do with this. Right off the bat in the book, Koenig spreads out the “rules of Columbo” – the constant components the expectation of which keeps watchers returning consistently. Each episode is, obviously, a transformed secret; Columbo was, in the event that not the absolute first, then probably the earliest adopter of the “howdunnit” approach. Class paradigms are additionally transformed. Pretty much every one of the killers is elite who kill without risk of punishment, buttressed by a resolute privilege. This is a subsidiary of the show’s vision of Los Angeles as a wanton, ethically uncertain jungle gym of Haute société. The killings, Koenig states, “would happen in a disinfected, nearly dream Los Angeles, without shootouts, vehicle pursues, sting operations, or whores. In their place would be masterful houses occupied by legitimate, haughty experts to give a sharp difference to the diverse analyst.” So empowered are these “haughty experts” that they become persuaded they can pull off the killings if by some stroke of good luck they can develop the ideal homicide, conjoined to an impermeable plausible excuse. Along these lines it turns into a round of orchestrating the chess pieces, arranging the cards so that each case appears to be from the beginning unsolvable.

However, what the crooks can’t represent is the inventiveness of the glass-peered investigator. Columbo could appear to be simply one more old folk, tucked behind a ratty coat and driving a beat-down lemon around the rebellious L.A. roads. Be that as it may, his nose for a story’s free strands is mysteriously exact. It’s thus that some gauge the achievement or disappointment of every episode against its “pop” – the conclusive second in the last scene wherein the one remaining detail the killer hadn’t remembered to tie up is brought out by the criminal investigator and left seething in the light. On the off chance that we acknowledge this “pop”- weighty rubric, episodes like “Murder fair and square” – coordinated by a 24-year-old Steven Spielberg no less – and “Negative Reaction” – visitor featuring Dick Van Dyke as a picture taker who imagines maybe the most perfect wrongdoing in any Columbo – stand apart as without a doubt the series’ most noteworthy accomplishments.

However extraordinary as they seem to be, I’m more disposed toward episodes like “Reasonable for Framing” or “Any Old Port in a Storm.” Episodes that are so extraordinarily acted, scored, altered, and shot – are, at the end of the day, such masterpieces of older style realistic craftsmanship – that the actual wrongdoing sinks away underneath the episode’s visual, arousing, and sensational frisson. Episodes that merge high and low workmanship with flawless mindfulness. Episodes that keep you alert and aware.

Be that as it may, the exploration is obviously exhaustive and, every now and then, vivid. All things considered, the world in 1971 is an altogether different one from our own. It’s a universe of reruns and Saturday night network films. It’s a universe of “wheels” – a series where different shows are given revolution across a similar week after week time allotment, now and then under an umbrella title. (Columbo was a piece of the NBC Mystery Movie wheel from 1971 to 1974, turning with McCloud, McMillan and Wife, and Hec Ramsey.) It’s a world with such a scarcity of serviceable substances that unholy side projects like Mrs. Columbo, featuring Kate Mulgrew, get greenlit – for two seasons. Also, as Koenig so charmingly subtleties, it’s a universe of diva entertainers and, surprisingly, more obsequious makers. “We will lose the entertainer. Get to the Beverly Hills Hotel and kiss Oskar Werner’s butt,” says one maker, cited by Koenig. It doesn’t make any difference who, or why, for sure he was in any event, discussing. The statement says everything: It’s a time where you’d need to kiss Oskar Werner’s butt just to get an episode made.

Koenig’s examination rouses specific snapshots of disclosure that are to the point of making the peruser venture back and perceptibly pant. Minutes that recommend what might have been, for sure fortunately was never. Koenig reports, for instance, that Brian De Palma was in line to coordinate a Columbo in which the executioner is a gloomy author who, standing four foot nine, is on the whole in light of Truman Capote. Whenever De Palma couldn’t focus on the episode, he attempted to tee up his buddy Martin Scorsese to coordinate all things being equal. Whenever I read this I became frail at the knees, despite the fact that I was plunking down. However at that point, when we later catch wind of the proposition for an episode in which a psycho would capture Columbo’s better half, we maybe retreat into being cautious about what we wish for.

Self-clearly, Columbo’s significant other’s abducting was proof of a show getting to the furthest limit of its tie. Now, we’re six seasons in, and breaks are starting to arise. For one’s purposes, the monetary load of the show’s responsibilities can’t hold. Falk alone instructing the compensation he did generally ruled outshoot invades, regardless of Koenig giving us the feeling that 68 of the show’s 69 episodes went over the plan and over spending plan. Also, the show’s capacity to wheedle enormous name visitor appearances was financially hamstrung. However, when Dick Irving, at last, says “Nothing more will be tolerated!”, declining to agree to Falk’s requests, he realizes he’s truly just playing an awful cop. He should doubtlessly comprehend that the great cop will ultimately prevail upon Falk, that the unseemly arrangement will get marked, that the wheel will keep on rolling. What’s more, it did – Irving challenged Falk’s blustering after five seasons; Columbo completed for good after nine.

It is these later seasons that, for some, Columbo fans, leave an awful desire for the mouth. Such is the enthusiasm of the relationship Columbo instigates in aficionados watching the later seasons can, on occasion, want to look at a debilitated pet that should be finally given some closure. For example, as Koenig depicts the occasions paving the way to the show’s recovery in 1986, the peruser is really quite mindful that those occasions are just setting the ball moving on Columbo’s absolute bottom. “Falk communicated to [Simmons] that, similar to Link, he was against playing with the effective recipe,” Koenig reports. “He needed to resuscitate the show, not reexamine it. Falk took out the first, fraying waterproof shell. The studio found and revamped one of the first Peugeots, and furthermore observed a substitution Dog.” at the end of the day, they were absolutely out of thoughts. Yet, Koenig demands doing these late episodes equity, offering them the essential consideration and assiduity that his editorial impulse requests. The impact, obviously, is to draw out the account past sensible premium, so that by its last option organizes the book is swaying toward the end goal. “Falk had anticipated playing Columbo in his advanced age,” we read, “when the person’s distraction and different unconventionality could appear to be ordinary. However, his exhibition made the contrary difference. Columbo began to appear to be fringe feeble.” How totally discouraging!

The best disgrace about Shooting Columbo, notwithstanding, is that it neglects to address what precisely makes the show so great. For that, Columbo fans are in an ideal situation plunging into the all-consuming result of the Columbophile, a blogger (and over the top) who has checked on each episode and directed various explorers – with elaborate thrive and unmissable spirit for sure. Koenig, then again, would prefer to portray, historicize, describe. A large number of realities, some fascinating and some not thus, are introduced without examination. Also, maybe we ought to laud him for his obligation to the piece; for clinging tightly to his editorial capacities, and conveying them with proud sincerity. However, all things considered, there are still minutes where his editorial methodology falls delicate. The $100,000 cheat that drives Falk off the line, for instance, is introduced without the nearby assessment required by such a significant second.

Obviously, numerous Columbo fans wouldn’t fret. An exhaustive retelling of the numerous motions experienced in the creation of one of TV’s most prominent ever criminal investigator shows, the book is a fascinating piece of social history with regards to its own right. It will without a doubt satisfy its crowd. Yet, I’m more worried about the impact of those emotions on the eventual outcome. It’s not to the point of knowing why Donald Pleasance was given a role as Carsini for “Any Old Port in a Storm,” in light of the fact that when you’ve responded to that question, another is quickly summoned: how can it appear on the screen? What does it do to the episode? For what reason does or doesn’t it work?

However, at that point, the thing I’m pursuing is a totally unique possibility from that which Koenig has introduced to us. Unquestionably, a significant option has been added to the Columbo corpus. However, I can’t resist the urge to feel that an open door has been missed and that it will take another essayist taking part in a sincere course of stylish examination to genuinely give Columbo the dedication it merits. All in all, I needed a paean and on second thought got an update. That it’s a regularly fascinating and every so often extensive notice isn’t to the point of holding me back from needing the paean that Falk’s charming criminal investigator so lavishly merits..

Interested in this film, you can see more related other products Columbo here!